|

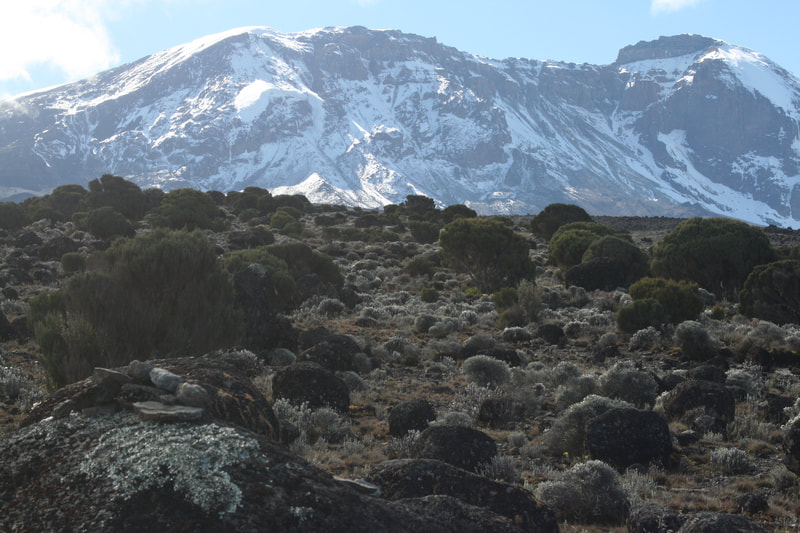

Like most who summit Uhuru Peak, we began our final ascent in darkness. The night before was cold, and we were underequipped with poorly rated sleeping bags, so we zipped three of them together and huddled inside to ward off the alpine chill. We came to Tanzania a few months earlier without the intent of climbing Kilimanjaro, so our gear was a mismatch of whatever we could find at local markets or borrow from the outfitter. After a few restless hours trying to chase sleep, we put fresh batteries in our headlamps and walked upward into the darkness. It’s certainly not a technical climb – I summited in Chuck Taylors with plastic bag booties on the inside – but the altitude made it a challenge as we searched for breath every few steps. As we reached the wooden sign signifying the highest point in Africa, we turned to watch the sunrise over the volcanic rim. All sensation of exhaustion evaporated as the sunlight painted the summit. We shared a beer – a Kilimanjaro Lager of course – which even when divided among several friends had an altitude enhanced effect. We then made our descent. The trek up the mountain took us six days, but the descent only took one and half. Without the need for acclimatizing to altitude, we turned our potential energy into kinetic energy and moved as quickly as our legs would take us. This pace afforded such a visceral perspective on the elevational patterns in biodiversity. In the span of a few hours we descended through at least 6 different ecosystems, each comprised of species most suited to the microclimates of a given elevation. I began the day on a glacier and ended it shirtless in forest with colobus monkeys in the canopy above. That’s one of the most beautiful parts of tropical mountains

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMichael Brown Archives

December 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed