|

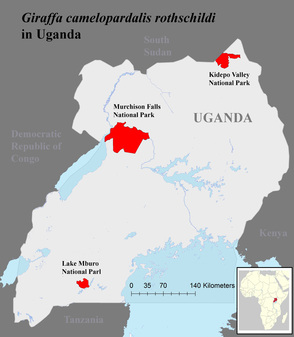

The Rothschild’s giraffe, Giraffa camelopardalis rothschildi, is among the most endangered of the nine giraffe subspecies with the current global numbers estimated at fewer than 1,700 individuals scattered across isolated populations in Kenya and Uganda. In recent history, giraffe in Uganda have been relegated to two distinct populations - Murchison Falls National Park and Kidepo Valley National Park. During late July of 2015, the Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) translocated fifteen individual giraffe from the Murchison Falls population to Lake Mburo National Park, aiming to create the foundation of a third population. During a previous trip to the field at the end of July 2015, a team from GCF and Cheyenne Mountain Zoo visited Lake Mburo National Park a few days after the giraffe were released in the Park This brief reconnaissance trip provided critical insights into the translocation process and offered an encouraging glimpse of the newly established population. The giraffe seemed to be settling down in their new, unfamiliar environment, but we wanted to collect a bit more information to examine these behaviors. This management decision to create a new population of Rothschild's giraffe in Uganda, in addition to contributing to the conservation of this endangered subspecies, provided a unique opportunity to potentially deepen our understanding of how giraffe behave in novel environments. Learning how giraffe distribute themselves over this unfamiliar terrain and how they interact with each other could generate a deeper understanding of not only general giraffe biology but also help to inform future conservation translocations. We had heard very interesting stories of groups of giraffe fusing and dissolving over different areas of the park from both UWA staff and eco lodges in the park, but without data to support these observations, the findings would not be able to transcend the realm of the anecdotal. During the that first post-translocation trip to Lake Mburo National Park, we had worked with some of the outstanding UWA staff to develop a basic monitoring programme to follow the health of individual giraffes and to begin to understand group structure in this newly established population. It quickly became clear, however, that without the necessary dedicated equipment, the rangers would not be able to collect the appropriate information to address these goals. Additionally, although Lake Mburo is a relatively small park - it covers an area of just over 260 km2 - the gently undulating network of hills and ridges provided ample opportunity for some giraffe to escape our observation from the road network, so we weren't able to verify the location and identity of all fifteen translocated giraffe. Indeed, we helped to lay the foundations of a monitoring programme during the July trip, but these efforts require consistent work, so we promised our counterparts in UWA to return with increased material and technical support. In early December 2015, we returned to the Lake Mburo National Park, bringing with us a load of requested equipment to supplement UWA's giraffe monitoring efforts. This assortment of equipment, which included two digital cameras, three binoculars, three handheld GPS units a laptop computer and rechargeable batteries, will allow the research and monitoring staff in the park to effectively track individual giraffes in the Park. By cataloguing spatially explicit digital images of giraffes and comparing them to a custom-built database of the known individuals in the park, rangers can map out their distributions and social associations over time. Having been fully outfitted for the task, we set out to the bush, ready to test the new equipment and implement the more rigorous monitoring protocols. With UWA rangers, Mihingo Conservation Fund and a photographer/writer duo, we drove the dusty track network of the park in pursuit of giraffe. Shortly after noon, we encountered the first group of nine giraffe, contentedly browsing on Acacia rather auspiciously situated just a few meters from the road. After finding the giraffe and recording the location of the group , we set into action, methodically photographing all individuals in the group. Giraffa camelopardalis rather obligingly have unique spot patterns which we can effectively use as name tags in identifying individuals. Unfortunately, however, these name tags are not symmetric and the spot patterns on a giraffes left side do not mirror those on its right. To make future surveying easier, we photographed all of the giraffe, associating left side and right side images. While photographing the giraffe, we were also carefully inspecting them for evidence of injury or disease and detailed their condition and locations to be entered into the central database back at the Park headquarters, to monitor the health of individuals over time. Having faithfully executed our protocol and content with the data collected from the first group of giraffe, we left the giraffe to resume their rumination and we again set forth to track down the remaining giraffe. The missing six giraffe proved to be a bit more elusive, and after several hours of searching, we nearly conceded for the day and began our drive back to base. On the return drive, as the sun was beginning its descent, we spotted a giraffe in the distance. Slowly, five other giraffe materialized from the surrounding shrubs, and in the golden light we photographed the remaining giraffe. Indeed, it was a day well spent and we slept well that evening with the knowledge that we had managed to survey the entire population. Over the next day, we returned to field again track down the giraffe, refine the protocol and perfect our techniques. The rangers very quickly mastered the new protocol and skillfully handled the equipment. With this newly implemented systematic data collection, UWA has the tools and the technical capacity to explore how giraffe, gleaning insights that can potentially be applied to giraffe in other populations. Additionally, with a developing citizen science program, tourists will be able to contribute information to this database. Every image captured by every long-lensed tourist can be a data point that can be used to deepen our understanding of giraffe ecology. The establishment of a viable giraffe population in Lake Mburo National Park is a long-term goal that depends on the reproductive outputs of this population. For long-lived species like giraffe (with a gestation period of nearly 14 months), assessing this goal may be years away; however collecting data on the associations and space use will help in

examining key environmental and social factors that contribute to these outcomes. This newly introduced systematic approach to monitoring giraffe will ensure that if any injuries or conflicts arise in the small population, park officials will be able to quickly detect and mitigate these issues and better understand best practices for future giraffe conservation work

1 Comment

|

AuthorMichael Brown Archives

December 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed